On Saturday, August 25, 1966, a community photojournalist packed his camera in his car and headed for the Seattle Center Coliseum. He was bound for a fateful rendezvous with The Beatles, the rock ‘n’ roll band whose music, films and off-stage statements had combined to effect deep-seated changes in youth culture around the world.

At a pivotal time in American history, as most middle-aged men spoke derisively of this rock band’s long hair and silly love songs, 44-year-old Anacortes native Wallie Funk sensed a powerful connection among the four British musicians and their fans.

According to HistoryLink.com, The Beatles flew out of Hollywood on a chartered jet that morning, landing at the Seattle-Tacoma Airport at 1:40 in the afternoon. Before the day was out they would perform two concerts, both featuring about 10 songs received by wild and boisterous audiences. Most firsthand reports, including that of Funk, agree that the music was barely audible above the din of the crowd.

For Funk, past publisher of the Anacortes American and at the time publisher of the Whidbey News-Times in Oak Harbor, there was nothing odd about his decision to join thousands of frenzied teens for this concert. After all, The Beatles’ music had quickly and continuously inspired a growing fan base since their U.S. debut in 1964. Their cultural “impact” touched the lives of virtually every family in the communities Wallie Funk served. In response to inquiry as to what prompted him to travel to a rock concert on that historic day, Funk said:

“The younger generation seemed to be forming new alliances with some extraordinary musicians. The Beatles were beginning to create an international stir. I was aware every place they went they were developing a huge youth – teen-age – fandom. People said, ‘I’m not going to have my kids exposed to this.’ It didn’t make any difference. They came.”

Another obvious attraction for Funk: the music.

“I recall pulling over in my car to listen the first time I heard ‘Eleanor Rigby’,” he said. “They had some great music with all of the elements: mystery, adventure, death and romance.”

Funk’s impactful career as a community photojournalist included many articles and photographs published as the result of spur-of-the-moment decisions. However, his coverage of The Beatles concert was conceived through thoughtful and careful planning.

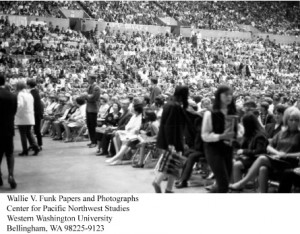

Capacity crowd at Seattle Center Coliseum

“One day I heard they were coming to Seattle,” he recalls. “I asked myself, ‘What do I do? How do I get there’? I had a (news)paper. I wanted our paper to have a presence.”

Telephone calls, one of the precious tools of his journalism career, included a conversation with Seattle Times photographer Paul Henderson. Another contact included Ad-VPR, the public relations firm responsible for The Beatles press conference. Among items of Funk memorabilia is a terse letter from Egan S. Rank of that firm. It read in part:

“This letter entitles the above-named individual to admittance at the press conference for The Beatles, which will be held at the Seattle Center Coliseum…”

However, among the “rules of procedure” in this letter that Funk admits to never reading, were conditions that would have prevented him from capturing the some two dozen concert photos that now rank among the most rare onstage images in existence. These rules went on to read: “This letter does not entitle you to admission to the concert, and you must purchase a ticket should you wish to attend.” And, “This letter DOES NOT entitle you to admission backstage.”

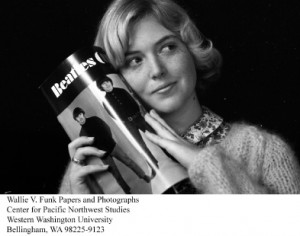

Oak Harbor High School student Scotty Nix

As Funk recalls, he took fellow photographer Henderson’s advice regarding the press conference, showing up to the southwest press entrance after first taking some photographs of the young people standing in line outside. Those frames included shots of Oak Harbor High School student Scotty Nix, who cheerfully posed with a concert program curled to her cheek. Local shots complete, Funk waited with the rest of the press representatives.

“When those at the door began to move, I moved with them,” he said. Photographers and reporters moved inside, down a corridor and into a large room. And there were The Beatles,” said Funk, “sitting elbow to elbow for an interview.”

The Beatles answer questions at a pre-concert press conference.

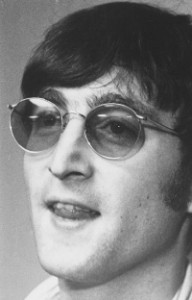

Funk asked no questions of the Fab Four, but it is obvious from the dozens of images from the press conference that he had staked out a prime position as a photographer. Only one or two frames included full faces of all four musicians, but there are a number of individual portraits, two of which have Paul McCartney looking directly into the lens of his camera. Other images reflect activity including the lighting of cigarettes (McCartney) and serious reflection in response to questions (most notably, John Lennon and George Harrison).

Funk notes that by journalistic standards, the press conference was not particularly meaty. Questions ranged from whether McCartney would be married to Jane Asher that night as rumored, to an inquiry as to Lennon’s motivation as songwriter/performer: “I’d like to know your motivation in this. Money?”

There was also reference to the so-called adverse publicity stirred in the U.S. when a months-old British magazine article ignited headlines because Lennon said in part: “We’re more popular than Jesus now.”

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer printed a souvenir edition to commemorate the band’s visit to Seattle.

Although the interview would continue to hound The Beatles – Lennon in particular – the Seattle press was satisfied to walk away with a few quotes on less serious subjects. With the press conference over, it was time to prepare for the concert.

Funk is short on details, as might be expected of an event that occurred four decades ago:

“When the interview was over, (we discovered) pandemonium in the Coliseum. I took a position,” Funk recalls, “elbows on the corner of the stage to brace me.”

There, using available light only, Funk captured images including a remarkable shot of the iconic McCartney-Lennon duo sharing the microphone. Unfortunately, his opportunity to record images from the performance was short-lived.

“I was there for just a brief time before a policeman said there was no picture-taking allowed during the concert,” said Funk. “But I didn’t care. I had just enough of them in action, mainly Paul and Lennon.”

John Lennon

Precious film in hand, Funk headed home. He developed the film, then moved into the darkroom to select and print images for what would become a controversial edition of his weekly newspaper. Funk made the decision to dedicate a full broadsheet newspaper picture-page to images from the press conference and concert. On the front page, above the banner, he paid tribute to The Beatles’ fame, positioning individual portraits of each of the four young men. As noted, Lennon’s earlier remarks referencing Jesus drew waves of criticism from Americans including some of the group’s fan base. A similar response from local newspaper subscribers was inevitable.

“The Christian right of Oak Harbor responded quite strongly,” Funk recalls. “One woman addressed a letter to City Hall saying, ‘Let Mr. Funk know I cancelled my subscription’.”

On the other hand, Funk recalls many conversations and calls of support. Among his archives is a handwritten letter from teen Carolyn Fosse, who wrote in part:

“I wish to express my deepest thanks concerning those beautiful Beatle pictures. I really am a big fan of The Beatles, as you already know. You know, I really wish more adults thought of The Beatles as you do. They really make me sick when some adults cut down The Beatles, and they don’t even know what they’re talking about. Most adults think only of how it was in ‘their’ day, and seem to reject the fact that the kids of ‘yesteryear’ and today are somewhat different.”

As he reflects today on that historic event, and on many other photo shoots outside of his newspaper’s zip code, Funk explains that he was driven by a desire to record slices of history on film. Over the coming decades, before his retirement from the news business, Funk’s extraordinary collection of photographs would include the Rolling Stones, rare documentation of the capture of Lolita the killer whale in Whidbey’s Penn Cove – and six presidents.

As he reflects today on that historic event, and on many other photo shoots outside of his newspaper’s zip code, Funk explains that he was driven by a desire to record slices of history on film. Over the coming decades, before his retirement from the news business, Funk’s extraordinary collection of photographs would include the Rolling Stones, rare documentation of the capture of Lolita the killer whale in Whidbey’s Penn Cove – and six presidents.

Newspaper partner John Webber often joked that Funk’s approach to photojournalism was a boon to the Kodak Corporation. Funk smiles at the memory of the complaint he heard so often – but then he shifts gears quickly and states with all seriousness:

“I’ve always had a strong passion to record by way of camera and film, not simply for the sake of taking pictures, but to capture something on film that translates the excitement of the time to my readership.”

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Funk, who recognized as a young man the critical need for notations and a trustworthy archive system for his work, also recognized the importance of finding a “proper home” for negatives, slides and prints. In fact, he has guaranteed continued access to his work via collections at Western Washington University, the Anacortes Museum and Island County Museum in Coupeville.

All photos of The Beatles © Wallie V. Funk Papers and Photographs, Center for Pacific Northwest Studies, Western Washington University, Bellingham WA 98225-9123. Copying/reproducing them without written permission from the copyright holder is strictly prohibited.