Paul Revere Williams may not have visited Anacortes, Washington, but the Tudor Revival home he designed on the city’s northeast tip stands as a unique achievement. It will be featured in the Anacortes Museum’s new exhibit on island architecture opening this May.

Paul Revere Williams may not have visited Anacortes, Washington, but the Tudor Revival home he designed on the city’s northeast tip stands as a unique achievement. It will be featured in the Anacortes Museum’s new exhibit on island architecture opening this May.

On Cap Sante, at the northern end of East Park Drive, a “mansion” was built for a wealthy California transplant, Luther Barrick, in 1928. Records from the Washington State Department of Archeology and Historic Preservation (DAHP) state: “The house was reportedly designed by a Los Angeles architect named Paul Williams.” Paul Revere Williams is the first known African-American member of the American Institute of Architects; inducted in 1923, he worked primarily in southern California. The home he designed for the Barrick family is the only known Paul Williams structure in Washington State.

A visit to the Paul R. Williams Project website offers insight into the architect’s biography as well as a gallery of his many works. He was born in a “vibrant multi-ethnic” Los Angeles in 1894, but lost both of his parents by age 5. He graduated in 1912 from L.A.’s Polytechnic High School, “the acme of present day high school educational results,” stated the June 21, 1912 Los Angeles Times. He began working for a Pasadena architect in 1914 designing luxury homes, eventually designing for numerous Hollywood celebrities.

Williams was raised by adoptive parents who encouraged his creative pursuits. “Williams’ great people skills, refined taste and ability were his most powerful weapons against his racial prejudice. His hundreds of clients valued his ability over any discomfort concerning race,” writes Deborah Brackstone, archivist at the Paul Revere Williams Project. “If I allow the fact that I am a Negro to checkmate my will to do, now, I will inevitably form the habit of being defeated,” Williams stated. One can imagine many chess-moves were necessary to find his path. Says Beverly Hills realtor Crosby Doe, “He was the Jackie Robinson of architecture.”

Williams was raised by adoptive parents who encouraged his creative pursuits. “Williams’ great people skills, refined taste and ability were his most powerful weapons against his racial prejudice. His hundreds of clients valued his ability over any discomfort concerning race,” writes Deborah Brackstone, archivist at the Paul Revere Williams Project. “If I allow the fact that I am a Negro to checkmate my will to do, now, I will inevitably form the habit of being defeated,” Williams stated. One can imagine many chess-moves were necessary to find his path. Says Beverly Hills realtor Crosby Doe, “He was the Jackie Robinson of architecture.”

He navigated occasional discouragement, like the high school counselor who voiced concerns about his ability to make a living as an architect. “Of course Williams proved his advisor wrong by finding clients of every color and by becoming a member of an elite group– an African American millionaire,” states Brackstone. “California represented an acceptance of both him, as an African-American, and his work,” says Robert Timme, dean of the USC School of Architecture. “Maybe Southern California was the only place he could have achieved all this.”

He navigated occasional discouragement, like the high school counselor who voiced concerns about his ability to make a living as an architect. “Of course Williams proved his advisor wrong by finding clients of every color and by becoming a member of an elite group– an African American millionaire,” states Brackstone. “California represented an acceptance of both him, as an African-American, and his work,” says Robert Timme, dean of the USC School of Architecture. “Maybe Southern California was the only place he could have achieved all this.”

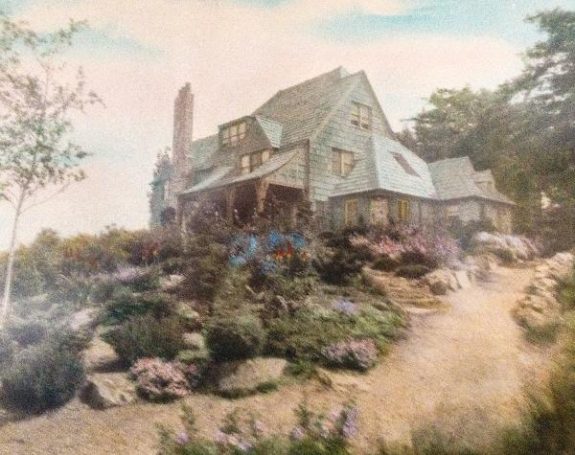

Luther Barrick, son of Union Metal Manufacturing Company founder Christopher Columbus Barrick, was a resident of Anacortes intermittently between 1927 and his death in 1946. Luther Barrick likely became aware of Paul Williams’ designs as a Los Angeles resident before his move to Anacortes. “Paul Williams had established himself as a master of combining the physical setting with historical architectural elements,” and Cap Sante’s Tide Point is a stunning location, well suited to William’s talents. “This house is significant as one of the finest examples of an Arts and Crafts style building in the city. It is enhanced by the masterful integration of the structure with the site,” states DAHP records.

Historians and other skeptics are already focused on the word “reportedly” in an above paragraph. The source in the 1987 report referencing Williams is likely Cap Sante resident Doris Packard, who is cited for providing an unrecorded interview to the DAHP inventory staff. This citation alone would be a thin link to proof of Williams’ design of Barrick’s Cap Sante home, were it not for the fact that Barrick was a client of Williams when he moved back to California in 1934. That home, now referred to as the Lloyd Bacon residence, establishes a second client/architect relationship.

Historians and other skeptics are already focused on the word “reportedly” in an above paragraph. The source in the 1987 report referencing Williams is likely Cap Sante resident Doris Packard, who is cited for providing an unrecorded interview to the DAHP inventory staff. This citation alone would be a thin link to proof of Williams’ design of Barrick’s Cap Sante home, were it not for the fact that Barrick was a client of Williams when he moved back to California in 1934. That home, now referred to as the Lloyd Bacon residence, establishes a second client/architect relationship.

Unfortunately, many details about Barrick’s business with Paul Williams are missing. The Williams’ archives – stored at a bank in Watts – were destroyed by fire in 1992 during civil unrest in Los Angeles following the Rodney King verdict.

The 3,700 square foot home at 201 E. Park is referred to in DAHP records as the Thomas Morrison residence, and is described as being Tudor Revival in style: “Characteristics of the style include the steeply pitched gable roof, the prominent chimney, small-paned windows, and imitation half-timbering.” Barrick had the home built for $20,000, according to the Anacortes American, five to ten times more than the “less pretentious” houses constructed in town that year, stating, “With the well-appointed surroundings, it is now one of Anacortes’ most beautiful homes.”

Los Angeles developer William Howden also hired Williams in 1928 to design a Tudor style house for one of his investment lots in Hancock Park, the description of which might as well be for Barrick’s home in Anacortes:

“The house Paul Williams designed for Howden incorporated many of the “classic” Tudor elements: shake roof, leaded glass windows, over-sized chimney and stucco with decorative half-timbers. To provide a homey interior, Williams used oak and pine for flooring, ceiling details and a large mantel. While the majority of Los Angeles homes had one bathroom, this house had three fully-tiled baths with tile lavatories.”

Paul Williams’ 50-year career produced thousands of projects, including Los Angeles International Airport, Saks Fifth Avenue and many more iconic buildings as well as homes for celebrities like Frank Sinatra, Lucille Ball, Lon Chaney and Zsa Zsa Gabor. According to the Los Angeles Times: “If you have a picture in your mind of Southern California in the 1950s and early 1960s, you are quite likely picturing a building created by Paul Williams.”

Paul Williams’ 50-year career produced thousands of projects, including Los Angeles International Airport, Saks Fifth Avenue and many more iconic buildings as well as homes for celebrities like Frank Sinatra, Lucille Ball, Lon Chaney and Zsa Zsa Gabor. According to the Los Angeles Times: “If you have a picture in your mind of Southern California in the 1950s and early 1960s, you are quite likely picturing a building created by Paul Williams.”

“He was completely undaunted by racism,” states Karen Hudson, author of books on the architect, and also his granddaughter. “Without having the wish to ‘show them,’ I developed a fierce desire to ‘show myself,’” Williams wrote in “I am a Negro,” his 1937 essay for American Magazine. “I wanted to vindicate every ability I had. I wanted to acquire new abilities. I wanted to prove that I, AS AN INDIVIDUAL, deserved a place in the world.”

At the northern end of the I-5 corridor, a lone example of Williams’ multidimensional design portfolio took hold on the rocky shore of Cap Sante. Would he have been welcome in 1920s Anacortes, at a time when Klan organizers were occasional lecturers at local churches? Presumably he would have navigated that challenge with his intrinsic tolerance: “White Americans, in spite of every prejudice, are essentially fair-minded people who cannot refuse to respect courage and honest effort. They will, therefore, give me an opportunity to prove my worth as an individual.”

The new exhibit at the Anacortes Museum will showcase the rich array and captivating history of distinctive and historic homes of Anacortes. To learn more about this exhibit or local historic preservation, contact the museum at coa.museum@cityofanacortes.org

Written and researched by Bret Lunsford, using the sources listed below

Sources:

http://www.paulrwilliamsproject.org/

http://www.usc.edu/dept/pubrel/trojan_family/spring04/williams1.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Williams_(architect)

Interview with Ron and Sheila Litzinger, current owners 201East Park Drive

Interview with Deanna Murray, past owner of 201East Park Drive